A torrid September for stock markets sent equities tumbling across the board, with the S&P500 ending the month down 4.87% and the quarter down 3.65%.

The Nasdaq, which has experienced significant tailwinds this year due to the performance of the “Magnificent Seven” tech stocks, fell even further, down 5.81% in September and 4.12% in the red for the entire quarter, as a higher for longer interest rate narrative took the momentum out of stocks that investors have been largely buying in anticipation of these companies’ growth prospects.

Canada’s S&P/TSX Composite Index fell 4% in September and 3% during the third quarter. Across the Atlantic, the FTSE 100 was the only equity market to gain ground during the quarter (up 3%) and September (up 2%). In contrast, the Eurostoxx 50 fell 10% during the quarter and 4.9% during the month, weighed down by fears of recession and ongoing European Central Bank hawkishness.

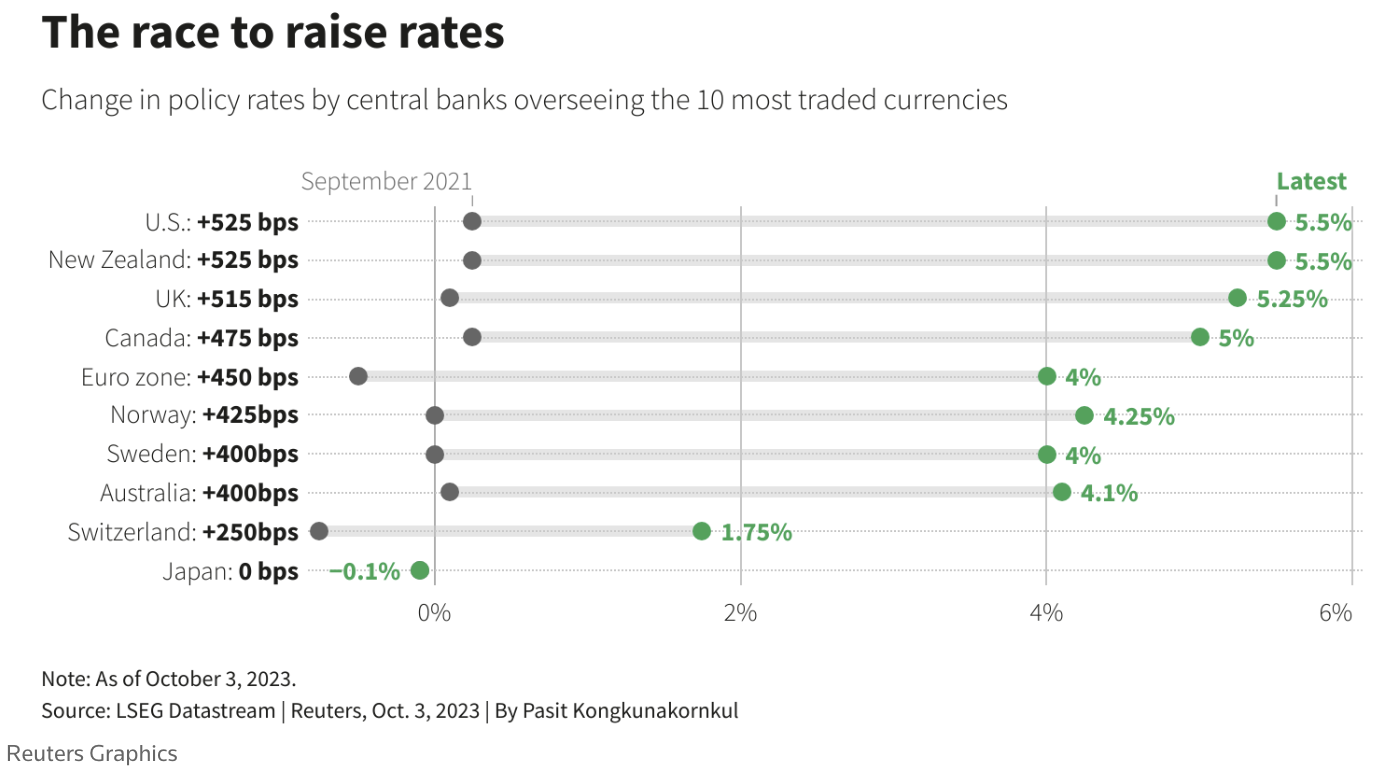

The third quarter saw a sharp swing in investor sentiment because hopes of a near-term decline in interest rates were replaced by an expectation that interest rates would remain higher for longer.

Although there has been clear evidence worldwide of disinflationary forces at work in bringing inflation rates off their heady highs, central banks remain committed to sustainably bringing down inflation to their target ranges. Nonetheless, rising oil and energy prices and ongoing geopolitical risks are adding uncertainty to inflation prospects in the year ahead.

These challenges contribute to a puzzling disconnect between the remarkably healthy economic data in most respects and consumer and investor sentiment about the economy. Though economies have proven surprisingly robust so far in the face of the steep rise in interest rates over the past few years, economists have observed a breakdown in the longstanding relationship between measures of consumer confidence and a basket of data that reflects the actual health of the economy.

Also, while core consumer inflation may have come down from its peak a year ago, it was still more than 4% in August, which is significantly higher than it has been for decades. With the oil price heading towards $100 a barrel and almost a third higher over the third quarter, it’s no surprise that consumers still feel the pinch of higher inflation. The Israel-Hamas war is expected to drive up oil prices. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has stated that Israel’s response to the Gaza conflict will ‘change the Middle East,’ and the previously promising progress in normalizing relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel has now been scuppered.

The shock to energy prices after the Russia-Ukraine war started last year triggered a steep increase in global inflation. Thus, the latest geopolitical flare-ups and developments in energy markets will likely prove the Fed’s next big challenge. A combination of record levels of oil demand, OPEC+ reducing production levels, and Russia’s decision to halt diesel exports to countries that have come to rely heavily on these imports threaten to become a toxic cocktail ahead of the Northern Hemisphere winter. Though Europe has imposed sanctions on diesel imports from Russia, which the region relies on heavily for various heavy industries and heating, the impact of Russia not exporting to the other countries will affect the global supply-demand balance with inflationary consequences for the energy price.

A reflection of the pressure on living standards is the plethora of strikes experienced across the US and Canada, with demands for higher wages in industries from auto workers to UPS delivery drivers to actors and writers in Hollywood. Even government workers in Canada were at the bargaining table, which is an unusual occurrence. These events add to inflationary pressure and make the job of central bankers in taming inflation much more difficult.

In fact, it isn’t a stretch to say the Fed and other central banks are in an impossible situation where they are damned if they don’t reduce rates and damned if they do. The global economy has held up reasonably well in the face of the highest interest rates in decades, with recession held at bay in the US and the UK and Europe under pressure but not experiencing the deep recessions expected at the outset of the year.

However, central banks are essentially trapped between risking crashing the economy and the stock market by maintaining interest rates at current levels or printing money to keep the global economy afloat, which is an exceptionally economically worrisome position globally. The Fed has indicated that the neutral interest rate is likely to be higher going forward, and investors have come to accept that a higher-for-longer inflation and interest rate environment is expected to prevail for the foreseeable future.

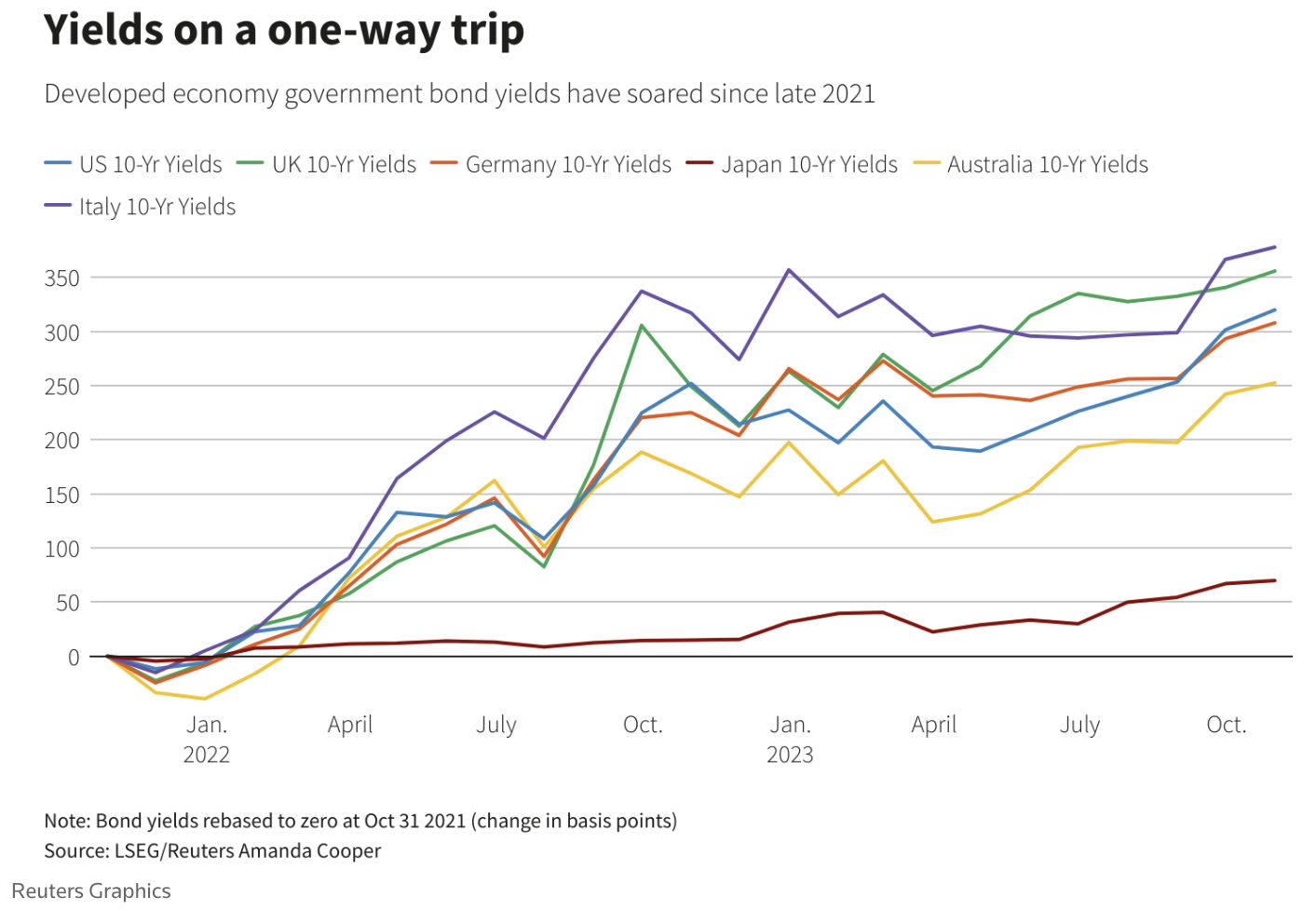

That has potentially grave consequences not only for equities but also for government bonds, which are experiencing a stock market-like bear market. During the third quarter, 10-year Treasury yields increased to 4.7% – a 15-year high. Since March 2020, bonds with maturities of 10 years or more have almost halved in value, according to Bloomberg, nearing the losses the stock market experienced during the dot-com bust in 2000 and in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.

The 30-year US Treasury has exceeded 5% intra-day for the first time in 15 years, and the yield on the 10-year Treasury, which is effectively the benchmark bond for the world, could touch that level from its recent 4.5% to 4.85% trading range.

Government bonds, traditionally viewed as safe haven investments, have attracted investors who viewed it as an opportunity to secure higher than usual long-term yields. That has prompted a sell-off in dividend paying stocks as bond yields rose. However, as high-quality dividend-paying companies have become cheaper, they can be a good way to augment income and enhance performance in a portfolio. As the sell-off continues, we are evaluating several opportunities globally.

Higher bond yields put added pressure on governments already struggling to fund public sector deficits that ramped up hugely during the Covid pandemic because of the stimulus packages put together to support their populations during a period of unprecedented financial hardship. Contributing to the bond rout are the bigger and more regular bond issues coming to market to fund the enlarged government debt burden.

Meanwhile, there were a couple of significant developments in the emerging market space during the quarter. To increase the power base of the so-called Global South, the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) economic grouping extended its membership base by inviting six new countries to join. These included resource-rich countries, namely Iran and Argentina, oil-rich Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt and Ethiopia.

Before holding its annual Summit in South Africa, BRICS members indicated they were pursuing an agenda of de-dollarization, which, though it may take time, does potentially mean a realignment of the geopolitical landscape is underway. ING Economics Chris Turner, Global Head of Markets and Regional Head of Research for UK & CEE questions whether the expanded group will accelerate the de-dollarization of trade payments, given that de-dollarization had been very slow to date and that any reduction in dollar market share has been a result of contracts denominated in the Chinese renminbi in Asia.

India’s standing on the world investment stage is also set to be uplifted by JP Morgan’s decision to include Indian government bonds in its emerging market debt index. The move, set to be implemented in late June 2024, has the potential to attract billions of dollars into the world’s fifth-largest economy because the index is so widely tracked by investment funds worldwide. At its maximum weight of 10% of the index, $24 billion of foreign money could find its way into the Indian bond market – a substantial sum.

Amid still high inflation, the performance of gold, traditionally viewed as an asset that provides a hedge against inflation, has been surprisingly muted this year. Some analysts ascribe the lacklustre 4% increase in the precious metal’s price to two factors: the expectations of a higher for longer interest rate environment and a result of a stronger than expected dollar.

However, gold remains an asset that may be worthy of consideration in a diversified portfolio, particularly for investors concerned about the uncertainty and volatility that prevail in financial markets.

Gold’s fortunes have been brighter in China, though, where a supposed “Shanghai effect” is seeing the gold price trade higher onshore than on offshore global markets. Bloomberg considers whether this is a result of de-dollarization as the People’s Bank of China opts to buy gold instead of US Treasuries to reduce its dependence on the US or whether it is a result of capital flight from China, with investors buying gold bars and coins to safeguard their assets from the financial woes that China is experiencing in the property market, the economy and listed financial markets.

Another economic hangover from the COVID pandemic that continues to linger is the gloomy fortunes of the commercial real estate industry, particularly the office sector in the US, where low occupancy rates are dragging down the sector’s performance. Property companies are struggling to find their feet in an environment where hybrid working arrangements continue, notwithstanding company efforts to get their employees back to in-person work. All indications are that the sector will continue to struggle in the year ahead.

Garnet O. Powell, MBA, CFA is the President & CEO of Allvista Investment Management Inc., a firm with a dedicated team of investment professionals that manage investment portfolios on behalf of individuals, corporations, and trusts to help them reach their investment goals. He has more than 25 years of experience in the financial markets and investing. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Wealth Advisors Network (CWAN) magazine. He can be reached at gpowell@allvista.ca