It was a year of two halves for commodity markets. The Russia-Ukraine war dominated the markets during the year’s first half, and macroeconomic factors were the driving force in the second half.

The onset of the war in Ukraine on February 24 sent energy and grain prices soaring to record highs. Then in the second half, macro-economic dynamics, such as a slowing global economy brought about by fast-rising interest rates and China’s Covid-zero policy, sapped demand and saw hard and soft commodity prices dwindle into year-end.

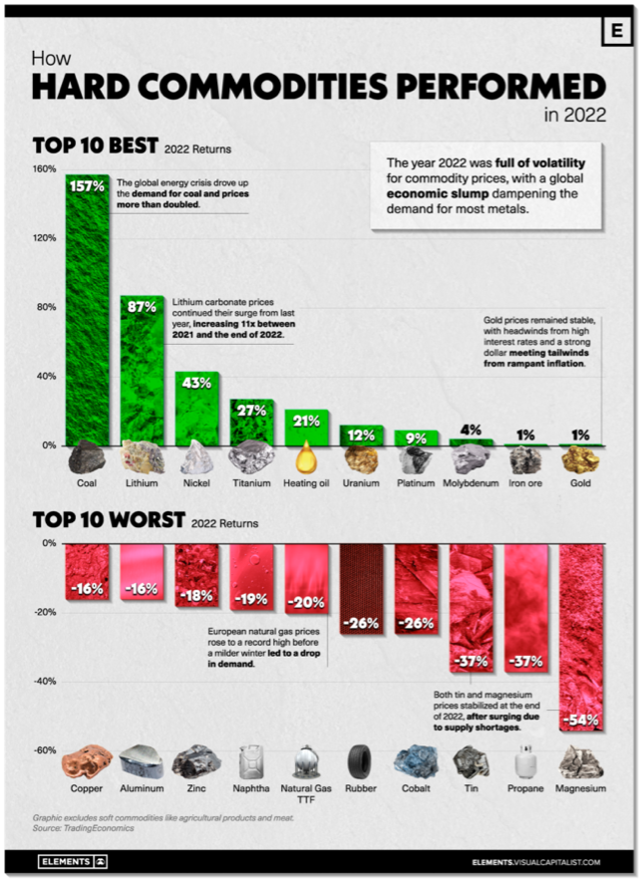

By the end of the year, coal came in as the best-performing commodity, 157% higher, as countries ramped up their coal production again in the face of the energy crisis. Lithium benefited from the demand for renewable energy sources and batteries, rising 87% and uranium, responding to a revival in interest in nuclear, advanced 12%. Precious metals platinum and gold managed to eke out gains, increasing 4% and 1% for the year, but for a large part of the year, they were depressed by the high inflation and rising interest rates.

Worst performers were the base metals and natural gas as demand waned as economic growth slowed and the outlook for 2023 became gloomier, with recession a likelihood in the advanced economies. Copper, viewed as a temperature gauge of how the global economy is performing, slumped by 16%, zinc by 18%, tin by 34% and magnesium, the worst-performing hard commodity, down 54%.

Meanwhile, soft commodities put in a mixed performance, with potatoes up 43.2% on supply shortages and speculation of market manipulation. Lumber was the worst performer, slumping 67.44% in response to housing market slumps in the face of steeply rising interest

rates. Soybeans ended the year 13.4% higher, while wheat ended the year at $7.92, eking out a 2.8% gain for the year as a whole.

Annual performance numbers don’t reveal the exceptional volatility in soft commodity prices experienced during the year. For instance, wheat prices reached a high of almost $13 a bushel in May before falling below $10 on April 1 and climbing back to $12.78 in mid-May. The grain ended the year just short of $8.

(source: mining.com)

(source: mining.com)

Natural Gas

Natural gas prices dominated the news in 2022 after the war catapulted British and Dutch natural gas prices 40% to 60% higher on the day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Europe’s almost complete dependence on Russian gas, distributed primarily through the Nordstream 1 pipeline, meant Russia could hold the threat of cutting the region off. Ultimately it did, after a few months in which supply was intermittent, and the Russian government explained away the repairs infrastructure maintenance.

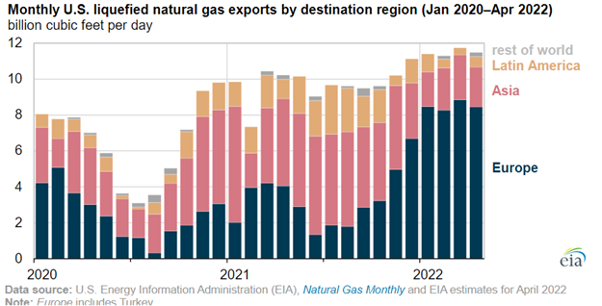

Natural gas TTF prices rose to Euro340 per megawatt hour in August but then eased back as Europe managed to build up reserves ahead of winter, and then the winter proved much milder than anticipated. US Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) supplies to Europe increased by 18% in 2021, and some 75% of US LNG exports went to Europe as the Biden administration made good on its commitment to help Europe navigate its energy crisis.

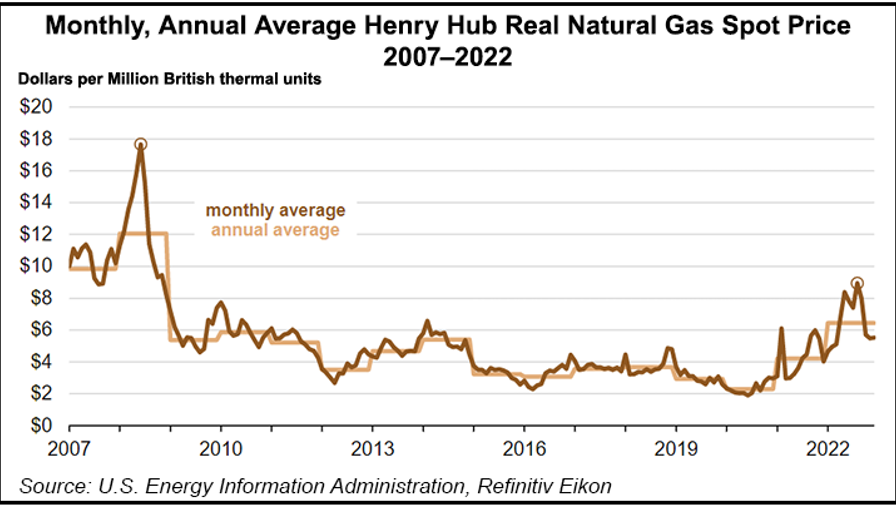

The Henry Hub gas price in the US averaged $6.45/MMBtu – its highest level since 2008 and 53% higher than in 2021, according to the Energy Information Administration. The price was also exceptionally volatile, ranging from $3.46 to $9.85/MMBtu daily.

Crude Oil

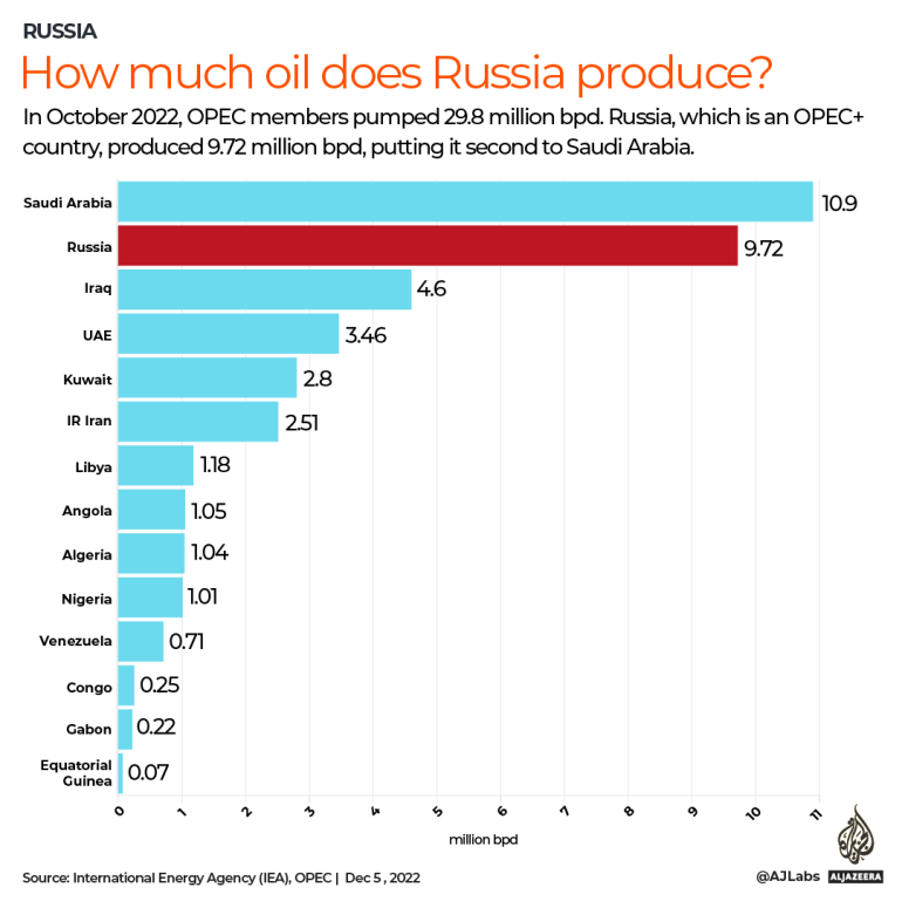

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the primary driver of crude oil prices in 2022 because Russia is so critical to world oil supplies. As the second largest producer of oil after Saudi Arabia and responsible for providing Europe with a third of its crude oil supplies, it’s no surprise that Brent crude oil shot above $120 a barrel during the week after the war started.

The oil price then traded above $100 until July before retreating further to span the $80 to $90 a barrel range for the second half of the year as concerns about economic growth and China’s Covid-Zero strategy weighed on consumer demand and travel.

In November, OPEC+ producers’ attracted much criticism for their decision to cut oil production levels by 2m barrels a day until the end of 2023. However, this decline in production levels was offset by Kazakh and Nigerian oil producers coming back onstream after overcoming operational challenges.

Later in the year, the G7, Australia and the EU implemented a price cap of $60 a barrel on Russian seaborne oil prices to drain Russia’s financial resources in the hope that it would no longer be able to afford the war. Russia has said it will not sell to countries imposing this cap and will continue exporting oil to China and India, which didn’t participate.

Soft Commodities

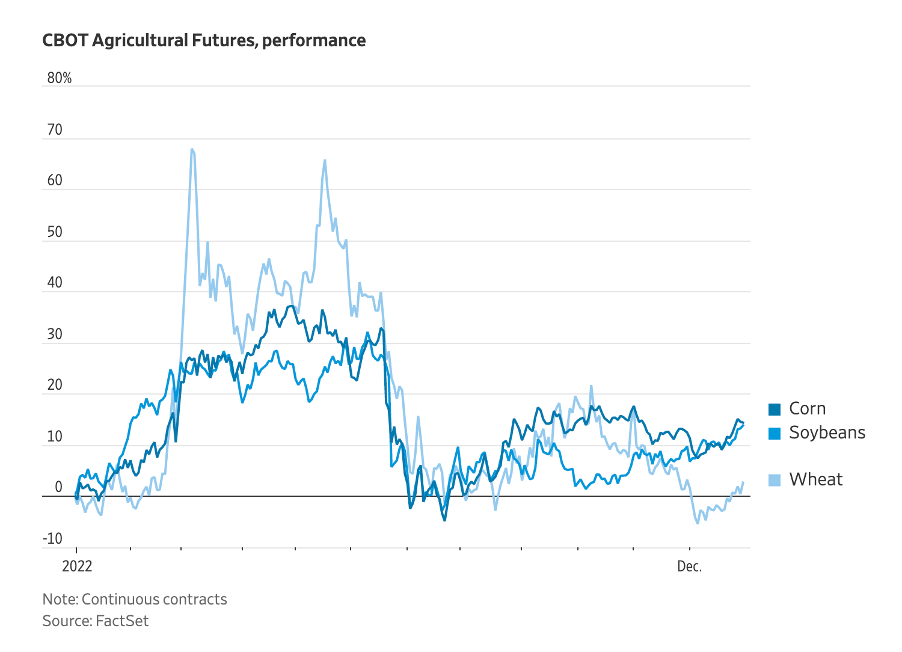

Grain prices shot up in the wake the Russia -Ukraine war, which saw Russia blockade Ukraine’s Black sea ports and prevent the country’s wheat from getting to the global market. Wheat and soybeans futures reached record highs. Corn futures climbed to their highest level since 2012. But prices then fell back from these heady levels as a cooling global economy dampened global demand. Russia entered an agreement in July last year to provide safe passage for grain exports from Ukrainian ports. The deal was then extended by 120 days in November but remains fragile.

As the graph below shows, wheat futures peaked at $12.94 a bushel in March, soybeans went as high as $17.46 in June and corn futures increased to $8.14 in April. Wheat ended 2022 2.76% higher year on year, soybeans 13.44% up and corn 14.37% ahead of 2021 levels.

Base Metals

Base metals were among the worst-performing commodities during 2022, depressed by mounting global growth concerns in the face of the aggressive rate hikes implemented by central banks worldwide. Most experienced double-digit declines, reversing their substantial gains the year before. Copper, which doubled in value in 2021, fell 14.47% year on year by the end of 2022. Steel declined 7.6%, zinc 15.9%, aluminum 15.3% and tin 36.2%.

The outlook for base metals remains uncertain and hinges predominantly on how China’s economy performs this year. During 2022, the growth in the world’s second-largest economy fell to 2.9% – substantially lower than expectations of 5.5% growth at the start of the year.

The country’s Covid-Zero policy shut down entire cities for months, and ongoing property woes continued to detract from growth. But the outlook became brighter for base metals in December when it summarily removed its Covid policies in December and put in place monetary policy measures to stimulate the economy.

Precious Metals

Precious metals also experienced a volatile year, racing to record highs after Russia invaded Ukraine as investors sought safe havens. They then came off until the last quarter when the prospect of the US Federal Reserve pivoting away from its aggressive rate hike stance prompted rallies across the precious metal stable.

Platinum saw the most significant increase during the year, gaining almost 12% on strong passenger vehicle demand and stiffer vehicle emission legislation in China and India, which will increase demand for a metal that is a critical component of vehicle emission control systems. Supply is also constrained and likely to remain so in 2023. South Africa, which produces almost three-quarters of the world’s platinum supplies, is struggling with power constraints and wage pressures that could contribute to a global deficit in the precious metal this year.

Gold benefited from its safe haven status and inflation-hedging qualities in the wake of the Russian invasion, breaching $2,000 an ounce in the first quarter – a level last seen 19 months before. But the price then fell below by the end of the quarter. During the third quarter, the precious metal was weighed down by seasonal weakness and a strong dollar, falling to a 30 month low of $1,691. It managed to hold its own for the year, ending the year at $1,824.

Lumber

Lumber had a torrid year as housing markets felt the full impact of rapidly rising interest rates and 12 consecutive declines in homebuilder sentiment during 2022, according to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB)/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (HMI).

The appetite for home building dried up as mortgage rates doubled to as much as 7% in response to the US Federal Reserve raising its Fed funds rate to 4.25% and 4.5% in December – its highest level in 15 years.

Lumber prices fell off a cliff during the year, slumping 67.4% year on year in December. Much will depend on how soon and quickly central banks begin reducing interest rates this year. According to the NAHB, weaker housing conditions will likely persist in 2023 before reviving again in 2024, when a national housing deficit of 1.5 million units and lower mortgage rates should lift demand again.

Looking Forward

The outlook for commodities is dependent mainly on the same three forces that so profoundly affected commodity markets last year – the fight against inflation, the war and the state of the Chinese economy.

Many economists expect it to be another year of two halves. Still-high interest rates are expected to characterize the first half as central banks continue to prioritize the fight against inflation over their economies. During the second half, the monetary policy pressures are expected to ease up as central banks pause or even reduce rates, kickstarting the economy again and providing a positive underpinning for most commodities.

The impact of the war on commodity prices may have subsided since the first quarter of 2022, but the outlook for the war remains exceptionally uncertain, with no endgame in sight. An escalation in hostilities, a subject of concern after Germany agreed to provide Ukraine with tanks, would weigh on commodities, particularly those produced in the region. A cessation in the war would lift a significant geopolitical risk that hangs over the world, and commodity prices would likely respond positively.

China’s economic growth will determine demand levels for hard commodities, and the pace of growth will largely depend on whether Covid becomes a disruptive force again, either due to its exit from the Covid-Zero regime or because new variants enter the scene. Should the government continue stimulating the economy and Covid fades into the background, as it has worldwide, the outlook for commodities would become far more bullish.

Garnet O. Powell, MBA, CFA is the President & CEO of Allvista Investment Management Inc., a firm with a dedicated team of investment professionals that manage investment portfolios on behalf of individuals, corporations, and trusts to help them reach their investment goals. He has more than 20 years of experience in the financial markets and investing. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Wealth Advisors Network (CWAN) magazine. He can be reached at gpowell@allvista.ca