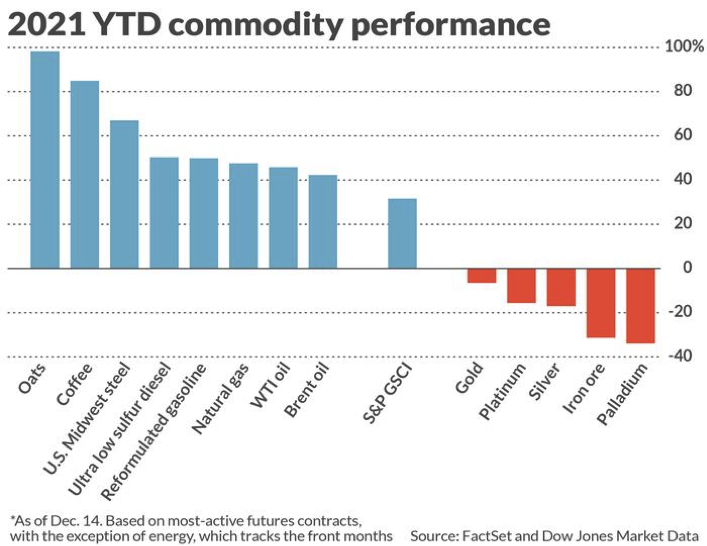

Surging demand, supply logjams, and adverse, or unusual, climate conditions in certain regions saw commodity prices put in their best performance since they bounced back from the 2008 financial crisis.

The surprising 40%-plus increase in fuel prices, in particular, reflected a world economy that continued to bounce back from the Covid-19 recession of 2020. Due to weather events, other commodity prices, such as oats and coffee, which topped the commodity price leader board, increased more than 80%. Commodity prices that ended the year in the red included precious metals, iron ore, and palladium.

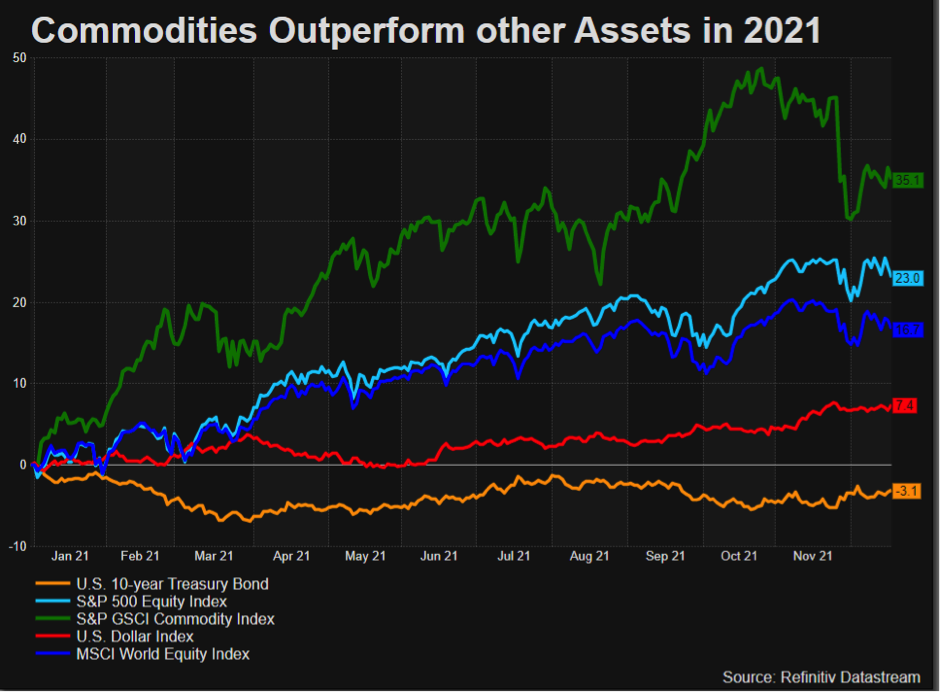

Price increases were so significant that commodities outpaced all other asset class returns, including global equities, which were on a tear last year. The S&P GSCI Commodity Index ended the year 35% ahead of the S&P 500 Index’s 23% gain. Global equities also put in double-digit performances, with the MSCI World Index up 16.7%.

Rising food and energy prices fed through to inflation, the effect of which was expected to be transitory and due to temporary demand-supply imbalances brought on by the pandemic recovery. However, price increase proved more enduring, with central banks likely to increase interest rates materially during 2022 to eliminate inflationary pressures and prevent inflation expectations from rising. Against this backdrop, expectations for commodity prices in 2022 are more muted though prices are still likely to remain above historical levels.

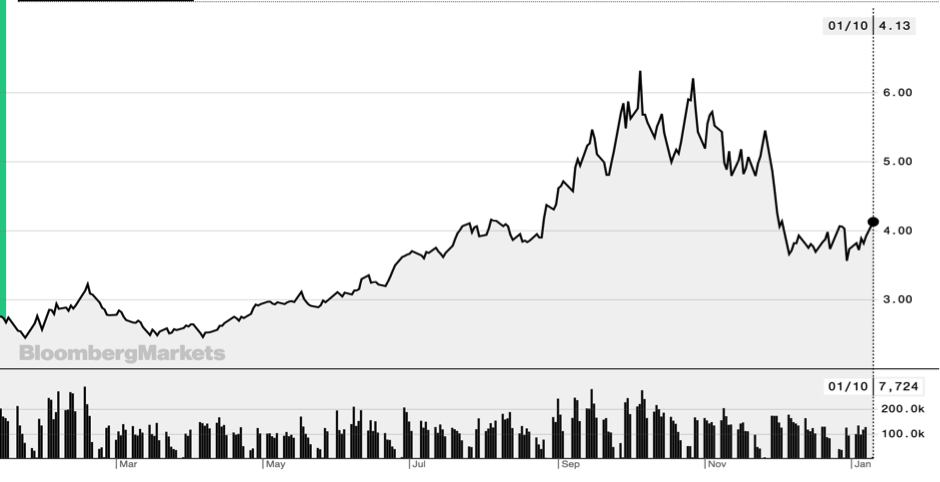

Natural gas

In a sign of the seismic shift underway in the energy industry globally, natural gas overtook oil as the most-watched commodity price in the last quarter of the year when a severe supply crunch hit natural gas markets ahead of the Northern Hemisphere winter. Prices soared from their 2021 nadir to an October peak as Europe battled to get hold of sufficient natural gas supplies after a wind-free summer in the North Sea and Russian supplies that failed to fill the gap. In the US, Nymex gas price increased 148% from January to its peak in October and then fell off after panic subsided, ending the year some 50% higher. Regional gas price moves varied considerably, with European gas prices, as measured by what is regarded as Europe’s benchmark gas contract, the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF), increasing to a record high of €119 on October 6 2021 – 230% higher than its early- March €36 per megawatt-hour level, according to International Banker.

Most significantly, the substantial increase in gas prices highlighted that natural gas is set to become the transition fuel as the world shifts towards a net-zero future. Of the three non-renewable energy sources, natural gas, oil, and coal, gas is the lowest emitter of CO2 and thus expected to become the stepping stone for most countries as they push to reduce their carbon emissions while building up sufficient renewable energy capacity in the decades ahead.

The International Energy Agency expects the Henry Hub spot price to average $4.58 from December through to February 2022 and then to decline through the rest of 2022. However, it expects prices to remain volatile, with winter conditions remaining a driving factor.

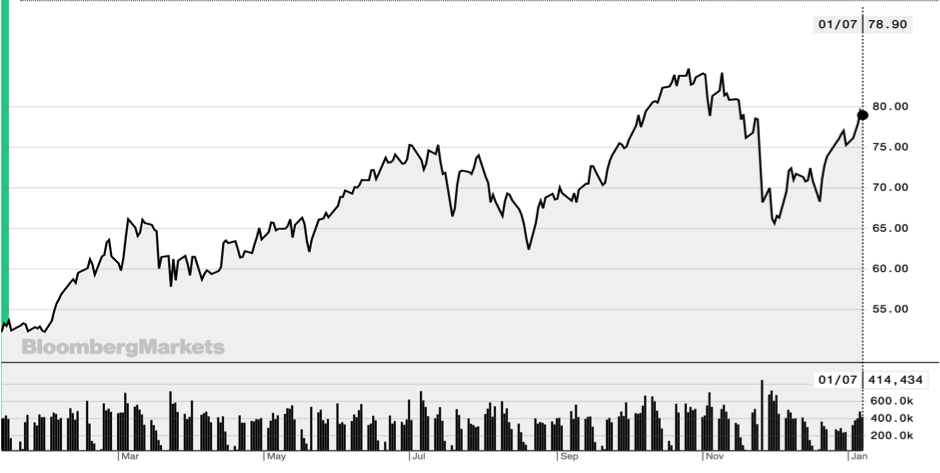

Crude Oil

Oil prices started the year below $50 a barrel before steadily rising during the first half of the year. The second half saw much more action, with the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil price racing up to a high of about $85 a barrel in late October in response to the opening up of the economy to travel and demand running ahead of supply. OPEC, which had pulled in the reins on production earlier in the year, resisted pressure from the US and other developed nations to up its production levels again. US President Biden responded by releasing 50 million barrels of crude oil from the country’s strategic reserves to ease price pressures. The increase in WTI crude price retreated to about $75 by the end of the year, still 55% higher for the year.

The International Energy Agency expects Brent crude oil prices to average $73 in the first quarter of 2022 but notes that the energy outlook remains uncertain in the short term.

Soft commodities

Soft commodities, including the prices of coffee, wheat, sugar, and oats, soared during 2021 as economic recovery demand and shortfalls in supply as a result of adverse weather conditions in key growing areas.

Coffee prices surprised to the upside when drought and frost in Brazil, a major coffee grower, saw coffee prices shoot up 76% in 2021, with the most severe impact on the premium Arabica beans. According to ING’s 2022 Commodities Outlook, the trajectory of coffee prices in 2022 is highly uncertain and will depend on the rainfall over the Brazilian rainy season.

The latest estimate for the Brazilian 2021/22 coffee crop from the country’s agricultural agency, Conab, is that production for the season has fallen almost 30% compared with the previous season.

Wheat and oat harvests were also on the receiving end of droughts in the US growing regions. As a result, oat prices made the biggest gains in the commodity sector, increasing almost 100% for the year – 8% of which was notched up in the first half of the year and the remainder in the second half. Wheat prices advanced 67%, while soybean oil prices were also a strong performer, reaching historical highs and ending the year 32% higher.

Corn and soybeans followed a different trajectory during the year, making most of their gains in the first half of the year and losing ground in the second half.

The USDA’s December World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report see no changes in the corn supply, with projected US oat imports increased for 2021/22 and the oats season-average price raised $0.05 to $3.70, based on continued tightness in supplies and strong cash prices.

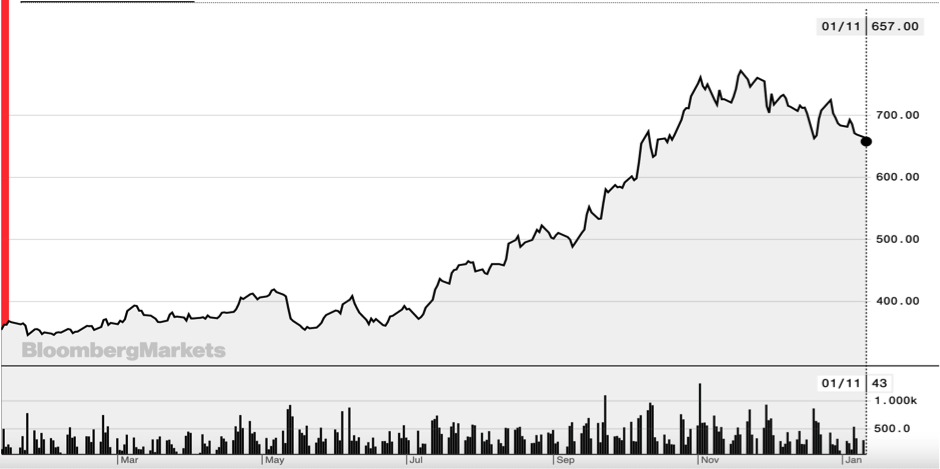

Oats CBOT USD/bushel

Wheat

Base metals

Aluminum was the second-best performer in the base metal stable, with prices increasing close to 45% for the year. The metal’s low carbon status will likely ensure prices remain elevated as the world transitions to a net-zero future and a massive structural deficit could arise.

The growing pressure on producers to adopt low carbon materials should sustain strong demand for low carbon aluminum, potentially leading to a massive structural deficit of aluminum. China will determine the deficits to a large degree as the world’s largest primary aluminum producer. The main risks are that the country hits its capacity cap and global demand for renewable vehicles and energy sources continues to rise unabated, which is highly likely.

Last year, China’s aluminum production fell short of expectations. ING expected growth of 8% year on year, but it came in at 3% due to China’s ‘dual-control’ mandate of energy intensity and total energy consumption.

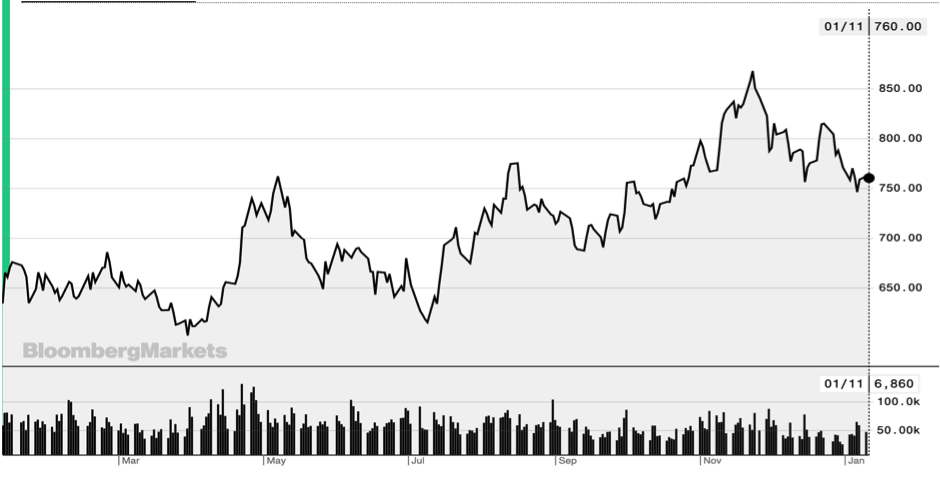

Copper

Copper prices also continued to increase, up 21% for the year, on the tailwinds of the transition to a green global economy. Prices rose to a record high of almost US$10,500 a tonne in early May and then fell back to around $9,000 a tonne. Copper supplies surprised to the upside, easing concerns about whether supplies will be sufficient to meet what is likely to be growing demand in the years ahead for now. Although there has been underinvestment in copper mines over the last decade, mine supply should increase as many projects get up and running this year.

Copper Comex US$/lb

Iron ore

At the other end of the base metal spectrum, iron ore prices slumped more than 20% last year – a figure that belies the significant volatility in the metal price during the year. After hitting an all-time high of $233 a tonne in May last year, iron ore prices more than halved from above $200 a tonne to less than $100 a tonne in the latter half of the year before regaining some lost ground.

The metal lost such significant ground in the second half of the year when Chinese steel production fell because industries had to operate on reduced hours in the face of coal shortfalls and electricity outages. Other factors that undermined the metal’s price were the Chinese government’s efforts to curb pollution and belatedly rein in property development to prevent the sector from overheating.

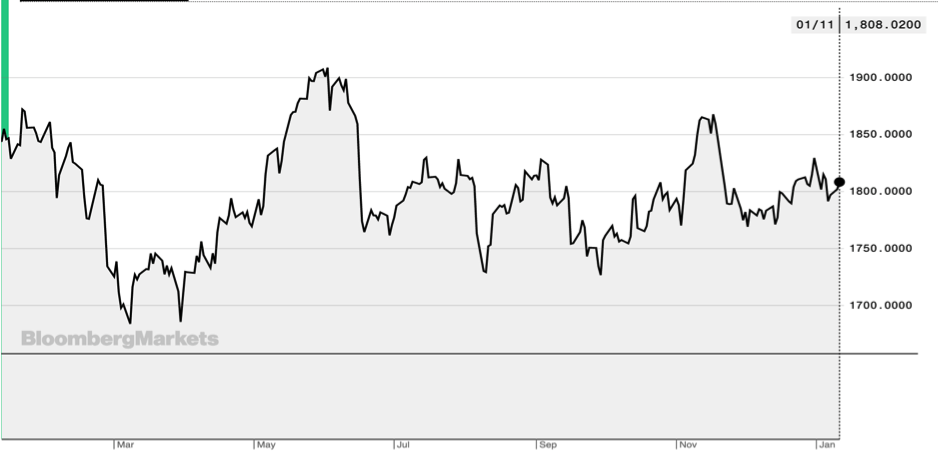

Precious metals

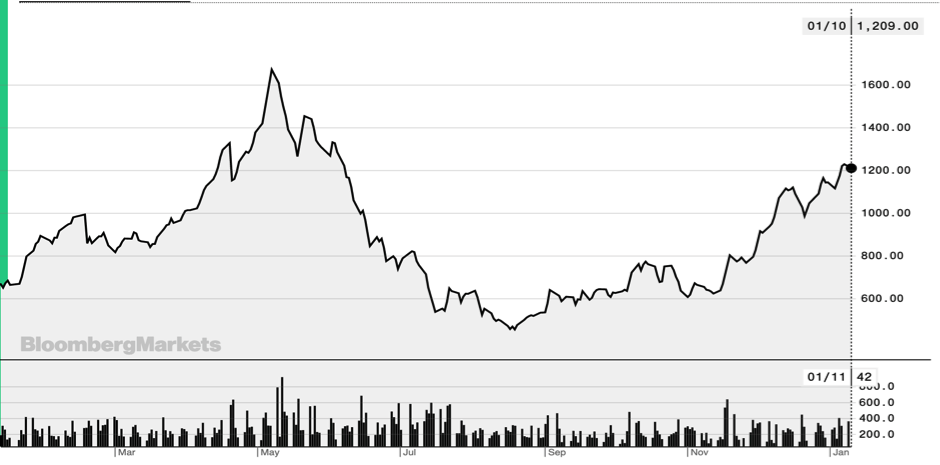

The precious metals languished alongside iron ore and palladium in the red for the year, with gold falling 5% in anticipation of monetary policy tightening this year and the interest rate increases that will go with it. ING notes that this marks gold’s first annual decline in three years after a positive start to the year when the price of gold broke above US$1,900/oz in May. However, that was when inflationary pressures were still expected to be temporary, and the US Federal Reserve was insistent that it didn’t need to take action anytime soon because prices would ease off as soon as the uniquely pandemic-related factors pushing up prices reverted to normal. After that, the precious metal’s price ranged between US$1,730/oz and US$1,830/oz until November when it broke above $1,850 again but then ended the year at just above $1,800/oz.

Gold spot price

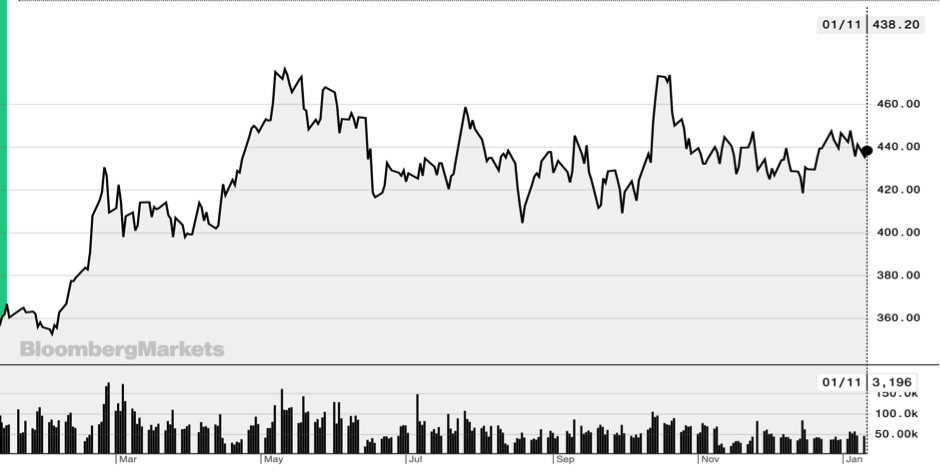

Lumber

Lumber prices also had a bumper year, increasing more than 75% in what has been described as a “lumber bubble.” Prices rose steeply in the first half of the year before pulling back and then increasing steadily again from November until the end of the year.

According to Lance Lambert in a Forbes article: “Production got behind during the lockdowns and struggled to catch up as both demand from DIYers and homebuilders soared. Eventually, it got sorted out this summer as sawmills upped production and DIYers got priced out of the market.”

Lumber – USD per 1,000 board feet

Looking forward

Commodities are still expected to be elevated this year but, barring further climate setbacks, like La Nina, which could bring adverse weather conditions in 2022. The World Bank says the 2021-2022 La Niña is likely to be “weak to moderate” and “slightly weaker” than last year. However, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has highlighted that “climate-sensitive sectors” such as agriculture, health, water resources, and disaster management will experience change.

To a large extent, other commodity prices will be determined by the scale of the ongoing economic recovery, particularly in China, and whether there are further Covid-19 variants that impact global activity. Just as important will be how fiscal and monetary policy decisions impact the size of the infrastructure boom and the global level of liquidity (and interest rates), respectively.

Garnet O. Powell, MBA, CFA is the President & CEO of Allvista Investment Management Inc., a firm with a dedicated team of investment professionals that manage investment portfolios on behalf of individuals, corporations, and trusts to help them reach their investment goals. He has more than 20 years of experience in the financial markets and investing. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Wealth Advisors Network (CWAN) magazine. He can be reached at gpowell@allvista.ca